One of my favorite productivity writers is Cal Newport, a computer science professor at Georgetown University. Before learning about digital minimalism, the perils of email, and “being so good they can’t ignore you,” I had been a struggling, but stubborn user of David Allen’s GTD workflow. But it was Newport’s re-envisioning of Allen’s protocols that helped me finally find a productivty system that worked for me. Like Allen, Newport writes (and talks) about prioritization with a growth mindset: not only what to work on right now, but what to work on this week, this quarter, or this year in order to move toward to the place where you want to be.

In seeking to determine what work is worthy of prioritization (or more importantly, one’s attention), Newport recommends asking questions like: “What are the skills in my area that are considered the most valuable? What skills are the most rare? What skills get people ahead?”

I realize that thinking solely with a growth mindset is problematic and, honestly, there are days I try to resist this (see also: Heather Havrilesky). Nonetheless, I want to grow as a person and as a colleague. The end result of this doesn’t need to be a promotion or a job with greater responsibility. It may in fact include the option to move into a position with a narrower scope. Instead, I like thinking in terms of what Newport describes as developing “career capital”:

“The traits that define great work require that you have something rare and valuable to offer in return” (So Good They Can’t Ignore You, p. 48).

So what are the skills considered most valuable and most rare in my work? And how do I cultivate those skills? (which, Newport goes on to tell us, are gained through developing a “craftsman mindset” and “deliberate practice”). In order to answer the first question, it’s important to define the scope: most valuable to whom? If I look just through the lens of my team, I might say “communication” or “trust.” If I expand the lens to include the whole of higher ed, I might say “research output” or “anti-racist work.”

For the purpose of creating reasonable and achievable goals, I’ve limited the scope of my reflection to “at my place of work” and “within the academic LIS profession.”

Growing within MPOW

I have been working in academia for 13 years, about half of that as a full-time librarian. In my experience, the skills that set apart those who succeed are less connected to the nature of their work and more to do with how they do it: kindness, project management expertise, and draft-making. Those who are kind to their colleagues, those who can articulate the entire life-cycle of a project, and those who put pen to page before pitching an idea are those who I judge to be successful. And by “successful” I don’t just mean get promoted or move up in rank: there are plenty of people who do that by being the pinnacle in their field, by being the only person around with a certain set of skills, or by riding on privilege’s coat tails. No, I also mean those who are respected by their colleagues and seen as a vital part of the fabric of a campus community. That is the place to which I aspire. So let’s look at each of these three attributes in more detail:

Kindness: This one is not difficult, but it does require intentionality: checking in with colleagues, regularly giving them shout-outs, sending notes of congratulations on recent projects. All these things are simple, but make a noticeable difference in workplace morale and interpersonal relationships.

Project Management: This one is more difficult and will require some deliberate practice on my part through learning and reflection. People who can outline the entire life-cycle of a project, break it down into manageable steps, and coordinate a team to complete it are rare. I’ve only seen this done well on a few occasions, but it has always left me in awe. People with brilliant ideas in academia are a dime a dozen: that’s why many of us are here! But making those ideas a reality within the context of a university’s infrastructure is not something grad school teaches you.

Draft-Making: Somewhat related to the skill above, the people who first put pen-to-page are often the ones whose ideas make it off the ground. Many times I’ve been in committee meetings where someone recommends a great idea, but it never leaves the discussion phase. The ideas that typically make it off the ground are ones where someone brought a written draft of a proposal. And even when those ideas didn’t immediately make off, they had more potential for coming back because, as a result of using a storage system like Box, it was more likely the file would be discovered again by someone else in the future. Records persist when ideas wither.

These are the three skills that I want to develop most this year. I am still working out a system for how best to track and assess, but I like Newport’s idea of counting the number of hours I spend in “deliberate practice” on any of these three practices. So maybe I’ll do that.

Growing within the LIS Profession

Using Google Scholar, I took a look at the publication track record for some of the LIS scholars that I admire and who write about topics in my field of work. On average, these scholars published 2-3 articles per year. This seems like a reasonable goal to work toward and one that I believe I could manage. It would require some significant changes in my work habits.

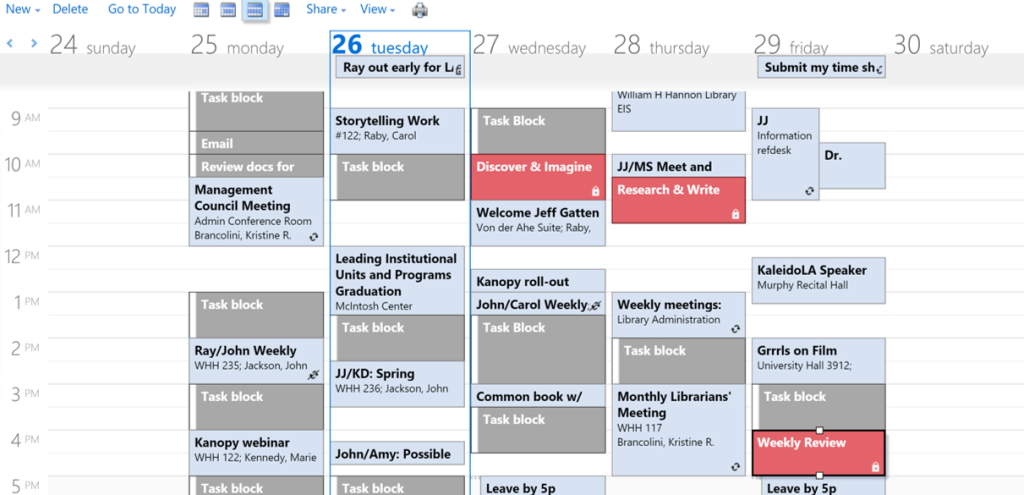

In order to make time for this level of research and publication, I estimated needing to set aside approximately 20-30% of my work time, leaving 60-70% for primary job responsibilities, and 10% for service work. That works out to about 10-12 hours per week focusing on research. It would also require more deliberate reading and evaluation of the research in my field to identify new areas for exploration (see also, Newport’s “research bible” idea, p. 113).

After only two months managing my time in this way, I have one article in drafting mode, one already submitted for publication, and another research project in the works. I was even able to quickly write up a case study for a colleague working on their upcoming book publication. Of course, this has meant making some sacrifices in my primary job responsibilities: I took a hard look (read: I time-tracked for 3 weeks) at how I was spending my time and determined a number of projects that were non-essential or could be delegated or dropped.

Which leads to an important point: in order to do any of this, I have to keep identifying ways to do less. I need to be intentional about how I use my time, how and when I allow my attention to be diverted, and honest with how much time a project will take to complete. Once you begin setting strict time limits for yourself, it becomes much easier to say no to new projects or tasks that don’t align with your priorities.

Final Thoughts

I am very lucky to be in a position where I can make these changes to my work. It’s one of the many reasons I love academia and MPOW in particular: personal responsibility, trust, and autonomy are granted to me and my librarian colleagues. Even though we don’t have tenure, we still have the flexibility to pursue areas of personal and professional growth. Academia fails in many areas related to work-life balance and there is room for improvement, for sure, but I can make this work.