For the last few years, I have been striving to de-center my job. I’ve stopped thinking of higher ed as a calling or a lifestyle. Instead, I’ve tried to focus on living in a more balanced way: one that still includes attention to craft, community, contemplation, and constitution, but in ways that are not grounded solely in my job as a librarian.

For this, and many other reasons, I loved Meredith Farkas’s latest post, “Stop Normalizing Overwork.” In particular, I liked this quote:

“Let’s stop being complicit in creating cultures of overwork. Let’s let structures that are built on our overwork, on our exploitation, fall apart. Real solidarity requires this. By refusing to overwork, we not only set an example for our colleagues. We make it that much less of the norm. It’s hard to fight to de-normalize overwork while you are continuing to overwork.”

A three-pronged solution

My own solution to the problem of overwork (in addition to therapy) came through the combination of task-blocking, autopilot scheduling, and quotas.

Task blocking is the process of determining in advance how I’m going to spend my time and then scheduling that work on my calendar. So if I have 5 major tasks I want to accomplish next week, I decide how much time I need to complete them and then schedule that time into my calendar before the week begins. If it turns out that I don’t have enough time in my calendar, I either (1) cancel something on my calendar to make room for it or (2) decide not to do that task.

Autopilot scheduling is the process of setting aside a specific block of time each week for a recurring task or class of tasks. For example, I know that I need at least 1.5 hours to plan out and schedule a week’s worth of social media posts, so I have a recurring meeting on my calendar for this work. Additionally, I know it takes about 6+ hours/month to create each issue of the library’s monthly newsletter, so I block off 1.5 hours each week and, if necessary, add more time if it seems to be taking longer than usual.

Quotas are weekly, monthly, or quarterly limits that I put on certain types of work. In academia, we often divide our work into performance, research, and service. I try to set aside no more that 10% of any given time period for service, 20% for research, and 70% for performance. Additionally, I limit myself to no more than three “big” projects at a time and then schedule those projects out over three semesters.

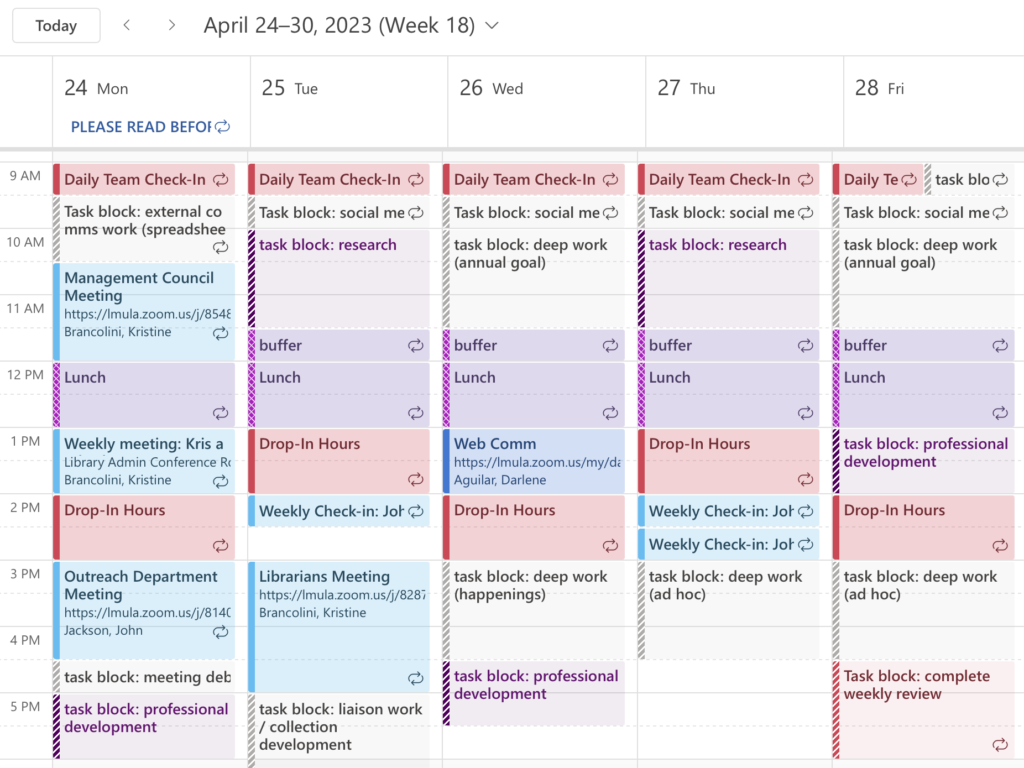

As a result of spending years fine-tuning this work, in addition to time tracking cyclical projects, I can tell you with relative accuracy what I’ll be doing in any given week. In fact, here’s what my calendar looks like 6 months from now for the week of April 25, 2023:

Unless the parameters of my job changes, I know I’ll be working on my annual goals. I know I’ll be meeting with my direct reports. I know I’ll be developing content for social media. I know I’ll be writing something for the library’s e-newsletter. I know I’ll need to spend time on my research. I know I’ll need to meet with people (“Drop-in Hours”). I know I’ll need to eat lunch. And I know something else (“ad hoc”) while probably come up. These time blocks could move around, but I know what work I need to do in order to do my job well enough.

Setting up guardrails

And therein lies the solution. I’ve pre-determined what I need to do to be/feel successful. I’ve set my priorities in advance. Any new projects that come up have to fit into one of these buckets. If not, then either: (1) I have to stop doing something I’ve already committed to, or (2) I say “No, I’ve already met my quota on meetings/ research/ liaison work/ ad hoc projects/ etc.”

My guardrails are set at 45 hours per week. If I cannot regularly fit my work into that timeframe, then something has to give: meetings, responding to email, or specific projects themselves. And since my boss and I have already set my priorities for the year in my annual goals, I have a legitimate excuse to say no to new ones.

This system does have its drawbacks. My colleagues find it difficult to schedule meetings with me. It also limits opportunities for serendipitous projects, but to be honest: those were always the problem. In academia, we don’t lack for good ideas. We lack the time and resources to accomplish them. At least with this system I can accomplish what I set out to do and still be able to completely shut off each evening and weekend. I’ll take that over easy meeting scheduling any day.

Final thought

It should go without saying that this is not a solution to the plague of overwork in academia. I’m of the cynical belief that universities couldn’t survive without the overwork of their faculty and staff. Not enough of us plan out our unit-level projects and commit those resources in advance. Instead, we tend to simply agree that Project X is a good idea and just move forward willy-nilly, carving out time along the way to the detriment of all our other commitments. I would love to see a more systematic and thoughtful approach to moderating the project load of an entire unit, instead of relying on individuals to figure it out for themselves. That said, if we all agree to stop being complicit in overwork, as Farkas calls us to do and as I have done in my own work life, then maybe our organizations will start paying attention.